Three-Dimensional Geometric Analysis of Bharatanatyam Postures: Understanding Dance Through Vector Mathematics

This article presents a mathematical view of Bharatanatyam dance movements through the lens of three-dimensional geometry and vector field theory. By examining the spatial relationships between body segments, we identify how classical Indian dance forms generate complex geometric structures including helicoids, toroids, paraboloids, and composite volumetric forms. This experiment demonstrates that Bharatanatyam postures operate as dynamic vector fields rather than static planar configurations, with limb extensions functioning as directed vectors with controlled magnitude. Through case study examination of specific poses, we establish that the dancer's body generates volumetric envelopes that simultaneously create multiple advanced geometric shapes.

Also published on Zenodo and can be accessed via this link

1. Introduction

Bharatanatyam, one of the oldest classical dance forms of India, has traditionally been analyzed through aesthetic, cultural, and performative lenses. However, the underlying geometric and mathematical structures that govern its spatial organization are not explored in great detail. This paper bridges the gap between dance theory and mathematical analysis by applying three-dimensional geometry and vector field theory to Bharatanatyam postures.

The fundamental premise of this analysis is that the dancer's body is not a solid geometric object, but rather generates three-dimensional shapes as volumetric envelopes traced by limbs, torso, and gaze through space. These spatial forms operate simultaneously and interdependently, creating complex composite structures that define the unique aesthetic and kinetic qualities of Bharatanatyam.

2. Vector Field Analysis of Bharatanatyam Postures

2.1 Identification of Vectors in Postural Configurations

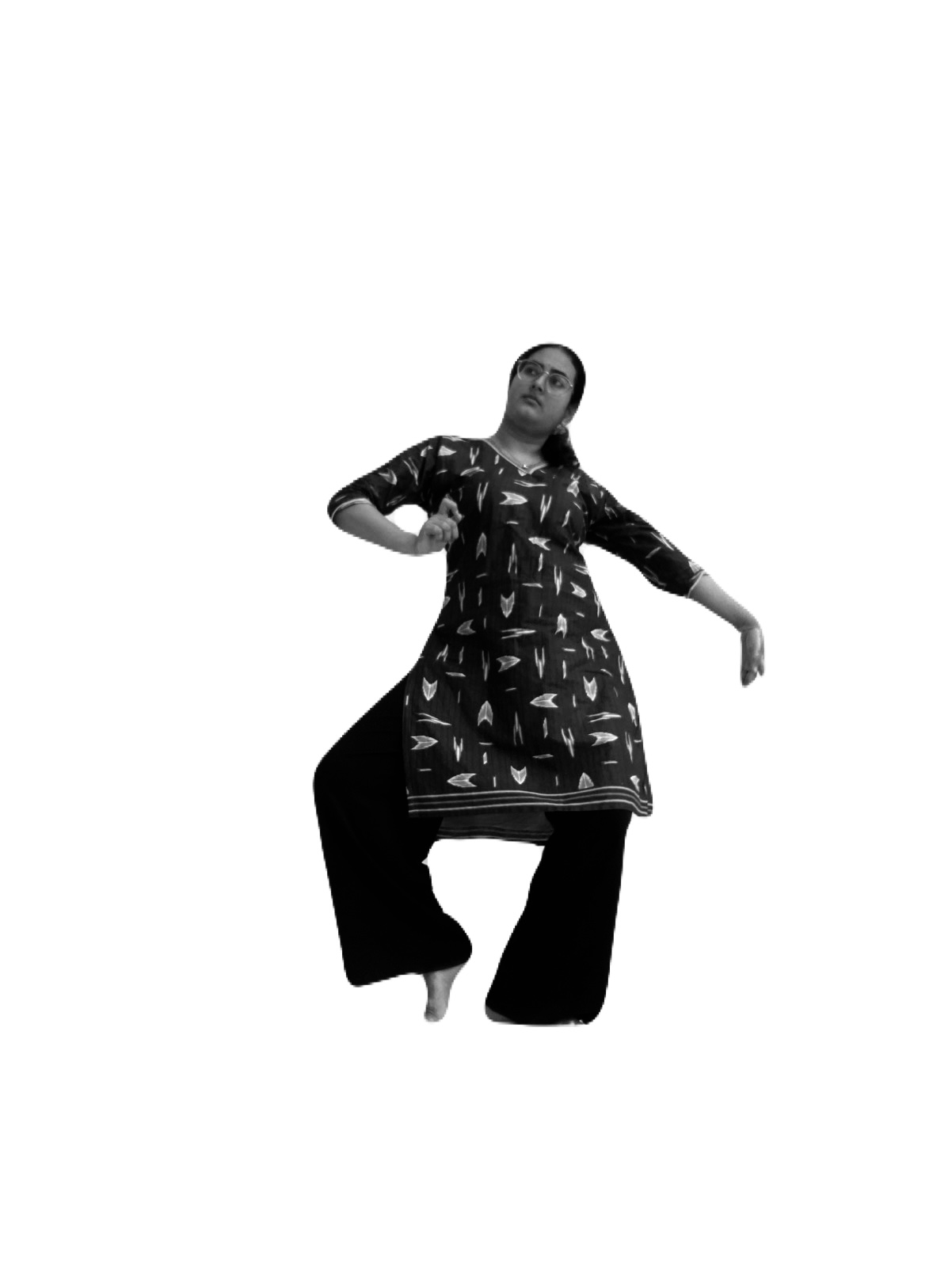

In Bharatanatyam postures, multiple body parts generate distinct directional vectors that operate within a three-dimensional coordinate system. Each posture exhibits characteristic vector components:

- Extended front arm: generates a strong horizontal vector

- Bent supporting arm: creates an inward, stabilizing vector

- Extended leg: produces a forward–downward vector

- Standing leg: establishes a vertical grounding vector

- Torso lean: contributes a diagonal vector

- Gaze (drishti/vision): projects a forward-directed vector

Each of these vectors possesses two fundamental properties:

- Direction: orientation in three-dimensional space

- Magnitude: determined by muscular engagement and extension

Figure 1: Bharatanatyam posture demonstrating vector field components. The extended front arm, bent supporting arm, extended leg, standing leg, torso lean, and gaze each generate distinct directional vectors operating in three-dimensional space.

2.2 Formation of Vector Fields

Rather than acting independently, these vectors operate simultaneously and interdependently, forming a coherent vector field that makes the dancer look polished and fluid. The extended arm projects energy outward, while the lifted leg extends spatial reach because the leg extends from the hip joint toward the foot (creating a vertical component along the leg's length), and forward because the lifted leg projects outward from the body into space (creating a depth component).

The torso tilt redistributes force diagonally, and the gaze aligns and amplifies the arm vector. Together, these vectors fill the surrounding space with organized directional forces, forming a vector field centered on the dancer's core.

Figure 2: Vector field formation in Bharatanatyam posture. Multiple vectors operate simultaneously, creating a coherent spatial force system. The extended arm projects energy outward, the lifted leg extends spatial reach, and the torso tilt redistributes force diagonally, forming a vector field centered on the dancer's core.

In this configuration, limb extensions operate as a three-dimensional vector field. The extended arm, lifted leg, torso inclination, and focused gaze function as directed vectors with controlled magnitude, collectively activating the surrounding space and producing a coherent spatial force system anchored at the dancer's center of gravity.

2.3 Three-Dimensional Axial Organization

The vector field occupies all three spatial dimensions simultaneously:

- X-axis (lateral): arm extension across space

- Y-axis (vertical): grounded supporting leg and lifted torso

- Z-axis (depth): forward projection of leg, arm, and gaze

This three-dimensional organization confirms that Bharatanatyam postures are fully volumetric, not planar configurations.

2.4 Vector Magnitude and Control

The clarity and coherence of the vector field depend on several technical factors:

- Full limb extension

- Stable grounding

- Controlled muscular tension

The balance between projection and containment—manifested through counter-vectors that maintain equilibrium—is a defining feature of Bharatanatyam technique. This balance ensures that high-magnitude vectors (such as the straight arm and pointed foot) are stabilized by counter-vectors (the bent arm and grounded leg), maintaining both dynamic energy and structural integrity.

3. Advanced Three-Dimensional Geometric Shapes in Bharatanatyam

Bharatanatyam postures manifest a range of advanced three-dimensional geometric forms rarely addressed in dance analysis. These shapes emerge not as rigid structures but as dynamic spatial volumes generated through movement and positioning.

3.1 Torus

The torus (doughnut-shaped volume) appears in Bharatanatyam through circular arm movements around the torso, creating an energy field defined by the arms and chest. This geometric form represents continuous flow and cyclical energy, characteristic of rhythmic loops around the body. The arm trajectories generate a toroidal spatial volume surrounding the torso.

3.2 Helicoid

The helicoid (twisted surface formed by rotation) manifests during spinal twists, neck and shoulder rotations, and turning adavus. This form represents dynamic rotational control, where the torso traces a helicoidal surface during rotational transitions.

3.3 Hyperboloid

The hyperboloid (hourglass-like structure) appears in postures such as araimandi with lifted torso, where the narrow waist contrasts with expanded shoulders and hips. This geometric form represents the tension between expansion and contraction, where the posture approximates a hyperboloid form, balancing opposing forces.

3.4 Paraboloid

The paraboloid (curved bowl or dome shape) emerges in poses with raised arms curving upward, energy lift from the chest, and upward-focused configurations. This form represents upward energy projection, where paraboloidal curvature directs visual and kinetic energy upward.

3.5 Elliptic Cylinder

The elliptic cylinder (extended curved vertical surface) appears when arm pathways combine with the torso axis, creating side extensions with rounded reach. This form represents elongation with curvature, where movement paths form elliptic cylindrical volumes.

3.6 Spherical Shell

The spherical shell (hollow sphere/energy boundary) manifests during expressive abhinaya, where mudra space around hands and face, along with eye and head coordination, creates a contained expressive energy field. Abhinaya unfolds within a spherical shell of controlled spatial energy.

3.7 Polyhedral Body Model

In strong angular poses with clear-cut arm and leg directions, the body approximates a polyhedral structure composed of intersecting planes, representing the body as a faceted solid.

3.8 Fractal Volumes

Fractal volumes (self-repeating patterns across scales) appear when finger geometry reflects arm geometry, or when foot patterns mirror full-body structure. This represents recursive spatial logic, where micro-level gestures replicate macro-level spatial forms, creating fractal volumes.

3.9 Temporal Dimension: Four-Dimensional Extension

When considering time as a dimension, temporal progression transforms static volumes into four-dimensional structures, where three-dimensional forms evolve through rhythm and temporal sequencing.

4. Case Study: Composite Geometric Analysis of Specific Postures

4.1 Methodological Framework

The following analysis examines specific Bharatanatyam postures to demonstrate how multiple geometric forms coexist simultaneously within single configurations. This composite approach reveals the sophisticated spatial logic underlying Bharatanatyam technique.

4.2 Helicoidal Geometry

In the examined posture below representing Lord Nataraja, helicoidal geometry emerges through torsional rotation. The torso rotates relative to the pelvis, with one arm projecting forward while the other opens backward. The spine remains lifted while the shoulders rotate, creating the defining condition for a helicoid.

Figure 3: Helicoidal geometry in Bharatanatyam posture. The torso rotates relative to the pelvis, with one arm projecting forward while the other opens backward. The shoulders rotate around a vertically stabilized spinal axis, generating a twisted spatial surface.

Geometric Mapping:

- Central axis

- Rotation: Shoulder girdle and arms

- Vertical stability: Bent front leg + grounded back leg

The body generates a twisted surface around the spine, even in momentarily static poses. Helicoidal geometry emerges as the shoulders rotate around a vertically stabilized spinal axis, generating a twisted spatial surface.

4.3 Toroidal Energy Fields

Although arms may appear extended linearly, toroidal volumes exist implicitly through opposing arm configurations. One arm projects forward while the opposite arm extends backward or laterally, with the chest remaining open and centered. Together, the arms trace opposing arcs around the torso, enclosing space.

Geometric Mapping:

- Central void: Torso

- Circular loop: Combined arm extension + shoulder openness

- Energy flow: Continuous, not broken

This creates a partial torus, common in dynamic Bharatanatyam stances. The opposing arm extensions generate a toroidal energy field encircling the torso, defining a continuous spatial loop.

4.4 Paraboloidal Curvature

Paraboloidal forms appear when one arm lifts upward or forward on a diagonal, the chest opens in the same direction, and the gaze follows the arm. This configuration forms an upward-opening curved volume, characteristic of a paraboloid.

Geometric Mapping:

- Curved surface: Arm trajectory + lifted shoulder line

- Direction: Outward and upward projection

Paraboloidal curvature is formed as the lifted arm and open chest project kinetic energy outward from a central focal point.

4.5 Composite Three-Dimensional Structure

The examined postures demonstrate that Bharatanatyam configurations are not single-shape representations. They simultaneously contain:

- Helicoid: torsional rotation

- Torus: enclosed arm–torso energy field

- Paraboloid: directional lift and projection

Figure 4: Composite three-dimensional geometry in Bharatanatyam posture. This configuration simultaneously manifests helicoidal surfaces (torsional rotation), toroidal volumes (enclosed arm-torso energy field), and paraboloidal curvature (directional lift and projection), demonstrating the sophisticated spatial logic underlying Bharatanatyam technique.

This layering of multiple geometric forms is a defining feature of Bharatanatyam's geometric sophistication.

5. Discussion

The analysis presented in this paper reveals that Bharatanatyam postures operate as complex three-dimensional geometric systems rather than simple planar configurations. The simultaneous manifestation of multiple advanced geometric shapes—helicoids, toroids, paraboloids, and their composites—demonstrates the sophisticated spatial logic underlying this classical dance form.

The vector field approach provides a mathematical framework for understanding how directional forces organize space around the dancer's body. This framework reveals that postural clarity depends not merely on individual limb positions, but on the coherent interaction of multiple vectors operating in three-dimensional space.

The identification of advanced geometric forms such as helicoids and toroids in Bharatanatyam postures represents a significant contribution to dance analysis, as these concepts are rarely applied in dance scholarship. This interdisciplinary approach—bridging mathematics, physics, and dance theory—opens new avenues for understanding the structural principles underlying classical Indian dance.

6. Conclusion

In these postures, Bharatanatyam manifests composite three-dimensional geometry. Helicoidal surfaces arise from shoulder rotation around a stable spinal axis, toroidal volumes are suggested through opposing arm extensions encircling the torso, and paraboloidal curvature directs kinetic energy outward through lifted limbs and focused gaze. The dancer thus constructs complex spatial volumes rather than isolated static forms.

This geometric analysis demonstrates that Bharatanatyam's aesthetic and kinetic qualities emerge from sophisticated three-dimensional spatial organization. The application of vector field theory and advanced geometric concepts to dance postures provides a rigorous mathematical framework for understanding classical Indian dance, while simultaneously revealing the inherent mathematical beauty of this art form.